|

このDVDは、次の方法により、一枚当たり2千円の価格にて入手できます。

(但し、国内の発送先に限ります。)

This DVD is available for JPY2,000-/copy by following the steps below.

|

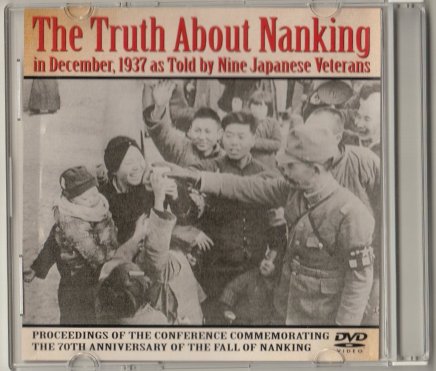

in December,1937 as Told by Nine Japanese Veterans

The DVD describes the 70th Anniversary Meeting commemorating the Fall of Nanking, held in Kudan Kaian Hall in Tokyo on December 6, 2007. Nine Japanese veterans who experienced the attack and occupation participated in the Anniversary Meeting and gave their testimonies. The DVD is the Engish version of the original, which is in Japanese.

|

このDVDは、次の方法により、一枚当たり2千円の価格にて入手できます。

(但し、国内の発送先に限ります。)

This DVD is available for JPY2,000-/copy by following the steps below.

|

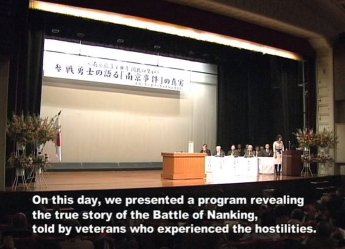

Seventy years have passed since the occupation of Nanking on December 13, 1937. On this day, we presented a program revealing the true story of the Battle of Nanking, told by veterans who experienced the hostilities.[Note]

- Surnames come first in accordance with Japanese conventions and written in capital letters.

- Roman numbers mean Battalion No., "i" means Infantry Regiment, and "D" means Division. For example, "III/2i, 6D" means 3rd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment, 6th Division.

[Contents]

- Opening Remarks by KASE Hideaki, Chairman

- Introductory Commment by TOMIZAWA Shigenobu

- Fierce Battle at Yuhuatai: Mr. FURUSAWA and Mr.NAGATA

- Entry into Nanking and Breaching of Gates

- A warm welcome from an old woman inside Nanking near Zhonghua Gate

- Never entered the Safety Zone - Situation in Nanking near Zhonghua Gate

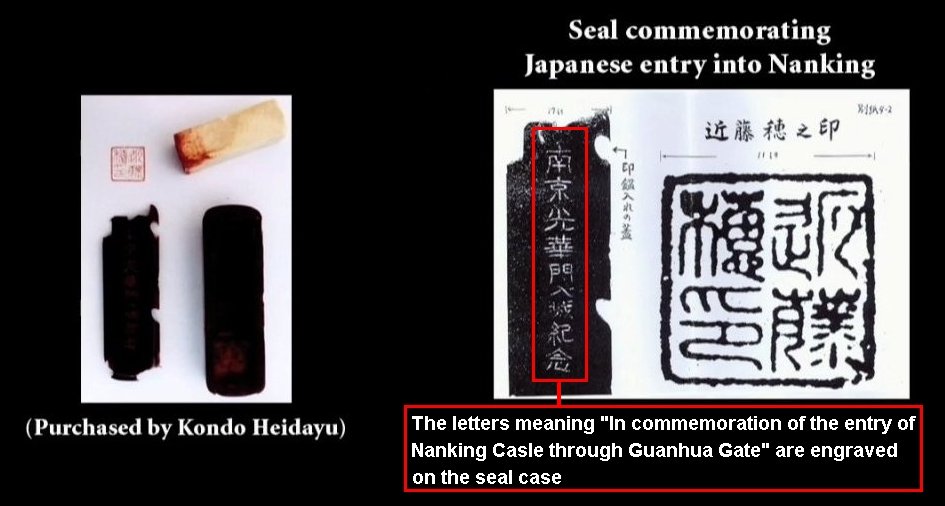

- Ordering a souvenir seal, sightseeing and shopping in Nanking

- No gunshots, no fires, A brigade’s sojourn, city sightseeing

- No Chinese soldiers’ corpses anywhere; Tour of the city; Situation near camp

- Not even one gunshot - The Safety (Refugee) Zone

- Questionnaire Results

- No assaults on civilians, murders, and looting

- Nanking residents reveal no animosity toward the Japanese

- Local procurement of food - Requisitioning governed by strict rules

- Prisoners of war escape, the prisoner problem

- Testimonies of 102 Nanking Veterans pronounced fantasy literature

Opening Remarks by KASE Hideaki, Chairman

Seventy years ago, on December 13, 1937, Japanese forces captured Nanking, then the national government’s capital.

After Japan was defeated in WWII, the allied forces lead by the U.S. convened the military tribunal commonly known as the Tokyo Trials, where Japanese military and political leaders were charged with war crimes.

The Americans had committed massacres: the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and the aerial bombing of Tokyo in March 10 in 1945 in defiance of the international law.

At the Tokyo Trials, the allies needed to demonstrate that the Japanese had perpetrated more heinous massacres. Since the Japanese had done nothing of the kind, the allies invented the Nanking Massacre.

As this year marks the 70th anniversary of the fall of Nanking we thought it would be an appropriate time to hold this conference.

Our featured guests are veterans of the battle of Nanking, who will tell us about the experiences during the hostilities and thereafter.

Most of the units assigned to the capture of Nanking were formed in the Kyushu and the Kinki and Hokuriku districts.

The veterans who will speak today, the oldest of whom is 97, still reside in those areas and have travelled quite a distance to be with us.

Please join me and welcoming these variant men who fought in the battle of Nanking and breached the city’s walls as they relate to their eyewitness accounts.

Introductory Comment by TOMIZAWA Shigenobu

First, I would like to say a few words about the nature of the conflict in the Shanghai and the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The hardship that was experienced by the Japanese in the battles of Shanghai at the beginning of the war continued to plague them throughout the conflict revealing a true nature of a war that was provoked by the enemy.

Heeding the advice of a team of German military advisors, Chiang Kai-shek built a great many sturdy pillboxes in Shanghai and its environments. He also amassed a huge stockpile of weapons and ammunition, and positioned tens of thousands of soldiers nearby.

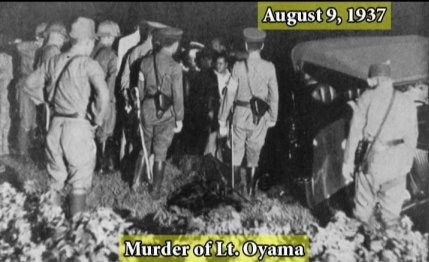

Fully prepared for the battle, the Chinese provoked the Japanese attack by murdering Lieutenant Ohyama Isao. The Second Sino-Japanese War had begun.

The Japanese rose to the challenge unaware of the serous difficulties that lay ahead.

Shanghai is bisected by the Huangpu River, a tributary of the Yangtze. The Japanese strategy was to land on the banks of the Huangpu and advance northward to the point where the river meets Suzhou Creek and involved crossing Suzhou Creek under enemy fire.

This 20 km journey was float with obstacles. It took the Japanese a full month to complete it.

After they forded the Suzhou Creek and the hostilities in Shanghai ended, the Japanese headed for Nanking.

Here the 330 km journey was effected in 30 days. Such struggles demonstrate that the battles fought in Shanghai were fermented by the Chinese and were not part of the campaign of Japanese aggression.

The Japanese were able to bring the Shanghai Conflict to an end thanks to the reinforcements in the form of the 10th Army, which landed in Hangzhou Bay, south of Shanghai and advanced to Shanghai.

The 10th Army landed in the face of enemy fire on November 5, 1937 at Hangzhou Bay.

Its men endured forced march after forced march in the effort to block the advance of Chinese troops at Kunshan, situated to the west of Shanghai. The divisions were of course unable to take their battalion guns with them, only infantry guns.

Anticipating a Japanese offensive and fearing their escaping route would be cut off, Chinese troops in Shanghai did not offer much resistance when the Japanese crossed Suzhou Creek. Instead, they headed for Nanking, and then came the Battle of Nanking.

I would like to offer a brief description of the conflict.

I will begin by stating two facts that prove the Nanking Incident is complete fiction.

In the first place the term “Nanking Incident” itself is a misdemeanor.

On December 13, 1937 the Japanese breached Nanking’s walls and entered the city.

Earlier, almost all the civilians remaining in Nanking had sought refugee in the Safety Zone.

The idea of the zone came from the international committee composed mainly of American missionaries in Nanking who hoped to prevent civilian casualties in the event of fighting between Chinese and Japanese troops within the city’s walls.

The Safety Zone, which occupied only a very small portion of the city, was to be strictly neutral.

On the evening of December 12, Chinese troops defending Nanking anticipated a full-scale attack by the Japanese on the following day.

The Chinese, including Commander-in-chief Tang Sheng-zhi, left their posts at Nanking’s gates.

They fled the city from its Northern Sector which they did not expect the Japanese to attack and scattered in all directions.

Soldiers, who missed the opportunity to escape, discarded their uniforms, changed into civilian cloths, and masquerading as civilians, infiltrated the Safety Zone.

As the result there were very few Chinese civilians or military personnel outside the Safety Zone.

[Note]

December 8, 1937 entry of Minnie Vautrin’s Diary states that “This evening we are receiving our first refugees and what heartbreaking stories they have to tell. They are ordered by Chinese military to leave their homes immediately; if they do not they will be considered traitors and shot. In some cases their houses are burned.” (p24, “The Undaunted Women of Nanking”)

Japanese Army sprayed notes of “surrender ultimatum” over the sky of Nanking on December 9 from a fighter plane pending 24 hours of response and began all-out assault on December 10. This clearly means that virtually all the civilians of Nanking were concentrated in the Safety Zone before commencement of the assault of the Japanese Army.

When Japanese soldiers entered Nanking, they noticed an eerie silence that pervaded the city. It was the sound of dead silence. How could a massacre or any incident have occurred in a city with no population?

According to charges brought by the Chinese at the Tokyo Trials, as soon as the Japanese entered Nanking they began killing every man and raping every woman they encountered.

Such accusations are obviously outright lies.

If there had been any sort of an incident, it would have occurred in the Safety Zone where the population of the city was concentrated, not all over the city as accusations would have it.

So what was happening inside the Safety Zone? The Americans who created the Safety Zone wanted to ensure that the Chinese inside it had sufficient food and shelter.

For that reason, the foreigners became extremely concerned about the number of refugees in the Safety Zone and the amount of food needed for them.

There were 200,000 Chinese in the Safety Zone. That population remained consistent until January 1938 when the international committee recorded it as 250,000. There was no massacre.

General MATSUI Iwane was sentenced to death by hanging for his alleged role in the Nanking Massacre. But the Americans’ record show that there was absolutely no decline in the population during General Matsui’s tenure.

I realize I ‘m impressing this point, but I want to make it absolutely clear that there could not have been mass murders in the Safety Zone.

These two facts prove decisively so that there was no massacre anywhere in Nanking. If there had been, it would have been perpetrated in the Safety Zone. But the population there never decreased.

I’m convinced that the veterans who will address you today will support my theories.

Thank you very much.

(Moderator's Comment)

I’d like to talk about the events that transpired after the hostilities at Shanghai described earlier in Mr. Tomizawa’s introduction.

When Nanking was practically in sight, the Japanese were confronted by a seemingly insurmountable challenge.

Breaking through the Nanking defense forces realign at Yuhuatai outside Zhonghua Gate and at Chunhuazen east of Zhonghua Gate.

It was here that the Japanese again encountered pillboxes for the first time since the Shanghai Conflict.

We will be hearing the testimony of Messrs. FURUSAWA Satoshi and NAGATA Naotake, formerly with the 6th Division 13th Infantry Regiment from Kumamoto.

These two gentlemen are unable to be with us today. But Narrator NISHIMURA Koyu will read the testimony they prepared for us.

Mr. Furusawa was attached to the Kumamoto Regiment’s 1st Company. He was born in July 1916 is now 91 years old.

Moderator: FUJIOKA Nobukatsu Narrator: NISHIMURA Koyu

Fierce Battle at Yuhuatai: Mr. FURUSAWA and Mr. NAGATA

FURUSAWA Satosi

Corporal, 1st Platoon

1st Company,

I/13i, 6DNAGATA Naotake

Private st Class, Infantry Gun Platoon,

1st Company,

I/13i, 6D[Note] Roman numbers=Battalion No., i=Infantry Regiment, D=Division

Here is his testimony.

The battle began on December 10 and extended from Yuhuatai to Zhonghua Gate was extreme intense. We crossed the moat surrounding Nanking. Since we have been assigned to the extreme right flank where the fighting was no so fierce, this task was somewhat easier for us.

Then we set about capturing the city walls. The advance unit had endured bitter struggles. But we were responsible for the extreme right flank and they had paved the way for us.

The hill called Yuhuatai and town of Yuhuatai situated between the rivers were in ruins. Nothing remained due to the Chinese scorched earth tactics

From late night of December 12 until the morning of 13, the enemy fled Nanking closing the gate behind them. But the Chinese outside the gate bore the brunt of our attack, and unfortunately, they were killed by our gunfire.

Now I read Mr. Nagata’s testimony.

We left Jiaxing (嘉興) on November 19 and arrived in Yuhuatai on December 10.

Our journey was fairy easy. All our units traveled down a wide road to find which one is first to arrive. We encountered no enemy troops along the way and very few civilians.

We had to find food locally, which was not easy. We had to requisition food, but we didn’t have any problems with local residents since they had already fled the area.

The battle of Yuhuatai was rough. The 3rd battalion advanced at the extreme left flank, where they were strafed by enemy machine-gun fire.

After the fighting ended I went to inspect the enemy pillbox. I discovered to my horror a Chinese soldier inside. His legs were chained to it. He was compelled to keep firing his machine-gun until he was killed since he couldn’t escape.

(Moderator’s Comment)

In the military history of the Kumamoto Corps, there is a similar description of a Chinese pillbox written by Major General Sakai, commander of the 11th Infantry Brigade

The enemy wound chains around the exterior of the pillboxes, in which they fought in place. The pillboxes became the coffins of those who manned them. Major General Sakai described their fate as unforgivably and violently inhumane.

Entry into Nanking and Breaching of Gates

SAITO Toshitane

Sergent

18th Infanty Brigade HeadquartersKITA Tomeharu

Corporal

I/7i, 9D

(Moderator)

After the Japanese broke through the last defense line, the next assignment was entry into Nanking.

First, they attempted to breach the gates. Each attempt resulted in desperate fighting. Now, Mr. Saito Toshitane will tell you about their strenuous efforts of the 36th Regiment from Sabae, the first unit to enter Nanking.

(SAITO Toshitane)

My name is Saito Toshitane. I was born in March 1921.

The 36th Regiment lead by Colonel Wakisaka marched through the night from Chunhuazhen (淳化鎮)arriving at the moat outside Guanhua Gate(光華門)at 5:00 am on December 9.

The surprised enemy sent up a flare and then returned fire with the canons and rifles. The 36th Regiment, with the aid of the division and army’s canons, prepared to charge Guan-hua Gate

At 5:00 pm on December 10, Regiment Commander Wakisaka issued orders to breach the gate. Having received the orders, Lieutenant Colonel Ito the commander of the First Battalion passed them on to Second Lieutenant Yamagiwa, who led the First Company into Nanking, followed by First Lieutenant Kuzuno of the Fourth Company. At 5:30 the Battalion Commander himself entered into the gate.

I understand that the Guanhua Gate was a double gate and it was very difficult to breach.

Yes, it was a double gate but we didn’t know that. We breached the first part of it, and then we were trapped between the two.

Some of the units climbed the city walls, raised the Rising Sun Flag, and yelled “Banzai!” three times. The enemy launched the counter-attack firing on the men who were trapped between the halves of the gate and the men up on the wall.

The fighting was fierce. Our men fought back with all our might but many of them were killed or wounded.

I heard an anecdote about the battalion commander’s glass-eye. Could you tell us about that?

The battalion commander encouraged his subordinates saying, “The news about the unit that gets through the Guanhua Gate first will reach Emperor’s ears. That’s why we have to defend our position to the death.”

We were encouraged all right, but eventually the battalion commander was wounded. He reached into his left-eye socket and removed the glass-eye he received from the Emperor as a reward for his valor in the 1932 Shanghai Conflict.

Then he handed it to a courier saying, “Deliver this to the regiment commander and tell him that it is the symbol of my determination to defend our position at Guanhua Gate to the death, and be sure to request more ammunition.”

We fought with all our might but the enemy fought back just as hard. At 9:00 pm, the commander was again hit by enemy fire and died a hero’s death. The battalion struggled at the Guanhua Gate until December 13 and we were finally able to gain complete control of it, because the enemy had retreated.

Than you very much

(Moderator)

Mr. Kita’s unit entered Nanking in an unusual way, not by capturing a gate but by breaking through a wall. He will tell about that now.

(KITA Tomeharu)

- Where in the wall were your points of entry? We have a map on the screen

Between Zhongshan (中山門)and Guanhua(光華門)gates, going towards Guanhua gate starting on the right, used A,B, and C.

- So you broke through a wall at those three locations.

The Uchiyama unit, the 5th Brigade, a heavy artillery unit used the canons to blast those holes.

- Would you show us where the three holes are on the map?

They seem the wall from the right; A, B and C

- Here they are; A, B, and C. How did you launch your attack at these three locations?

Unfortunately we failed with B, but succeeded with A and C. We entered the city through A.

- What about the enemy defense?

Oh, they opened fire on us right away. Some of them fired tracer bullets. There was a shower of bullets from above. But over time the number of enemy soldiers decreased. By the time we got into the city, there wasn’t one left.

- When was that?

About 5:00 am and on the 13th.

- Once you were inside the city, how far did you advance?

There was an airfield there. I don’t know its name, but we passed it on the south-side, proceeded a little further and then halted.

A warm welcome from an old woman inside Nanking near Zhonghua Gate

(Moderator) Mr. Furusawa, a member of the First battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment from Kumamoto.

As I mentioned earlier he could not be with us today. Mr. Nakagaki Hideo, a director of the Japan Nanking Society, was kind enough to interview Mr. Fukusawa.

We will now play the recording of the interview.

(Playing Tape Recordings)

- When did you break the city wall and entered Nanking?

I entered Nanking on December 14. I believe it was sometime after 1:00 pm.

- Which gate did you use?

Zhonghua Gate(中華門).

- What was the situation at that gate?

Zhonghua Gate was actually a series of four gates with cylindrical archways. The archway was packed tightly with sand bags, which the Engineer Corps had removed the previous day. We entered through the gate.

- According to other records, the 6th battalion used the lattice to scale the wall and occupied the Zhonghua Gate on December 13. But your unit passed through the gate on December 14 after the Engineer Corps removed the sand bags, meaning after the occupation commenced.

That is correct.

- What did you see when you entered the city?

I remember walking down a wide street but we didn’t see one enemy soldier. The city seemed empty. I didn’t see a soul.

- You didn’t encounter anyone in the city?

About 100m in from the gate, we ran into an old woman, who welcomed us with a home-made paper Japanese flag. I saw no one else.

- Just one person, then. Did you launch another assault inside the city?

No. After we advanced 100m, I heard “Halt! Retrace your steps and leave the city trough the gate.” Those were the orders so we left the city.

- What did you do then?

We camped outside the city.

- Where was your camp? What was the situation in the vicinity? Were there residents there?

Our quarters were outside Zhonghua Gate in private homes in the village north of Yuhuatai. We didn’t see any residents in the area.

- Then what did you do?

We received orders to advance to Wuhu (蕪湖). We were at the camp two or three days and then headed for Wuhu on December 17.

- Then your unit spent almost no time in Nanking.

That’s right.

- According to military records, the 6th Division proceeded to Wuhu starting out on December 15, the division commander left Nanking on 21. Was the fighting intense when you attacked the Zhonghua Gate?

I heard that the advance unit really struggled when they attacked the Zhonghua Gate. I also heard tat some of our men were killed during the attack on Yuhuatai.

- How was the Nanking Incident described to you?

At the time, I didn’t hear anything about it. When I first heard about it after WWII, I was astonished.

Thank you very much

Never entered the Safety Zone

Situation in Nanking near Zhonghua Gate

(Moderator)

Mr. Nagata still has his military diary. It contains the records of military maneuvers verified by all individuals in his unit.

This is what it looks like. Now I ask Mr. Nishimura Koyu to read selected portions of the diary.

(Narrator)

On November 5, 1937, we landed the Hangzhou Bay and advanced to the Kunshan area to block the escape route of Chinese troops fleeing Shanghai.

Then we headed straight for Nanking. On December 13, we fought in the Battle of Nanking. On 17th, we left Nanking bound for Wuhu.

That is what is written in the diary, but Mr. Furusawa added a few remarks.

My unit also entered Nanking. Once we proceeded to the location near the Safety Zone, but we soon turned back and camped near the southern city wall.

On December 17, we left the city through a different gate, not Zhonghua Gate. I think it was Shui-hsi Gate. Then we headed for Wuhu.

During that brief time, five days, I had peaceful interactions with nearby residents as well as friendly conversations with Japanese women.

Thank you

(Moderator)

As you’ve just heard, the Kumamoto Regiment spent only a short time in Nanking during which its men were either in deserted city or its peaceful outskirts.

The Kumamoto Regiment did not, in fact could not have possibly massacred great numbers of Chinese.

Nevertheless, the regiment’s commander, Lieutenant General Tani, was subjected to the military trial in Nanking where he was charged with the massacre of 300,000 Chinese allegedly perpetrated by his subordinates. He was pronounced guilty and shot to death at Yuhuatai.

It is clear beyond any doubt that he was innocent.

Mr. Furusawa told us that Yuhuatai was deserted having been reduced to ashes by the Chinese using their scorched earth tactic. Yuhuatai is situated south of the Zhonghua Gate. It is the city, today. Here is the photograph.

Ordering a souvenir seal, sightseeing and shopping in Nanking

KONDO Heidayu

Squad commander

10th Company,

III/36i, 9D

(Kondo Heidayu)

- After you took control of Nanking, where were you quartered?

After we captured Guanghua Gate, the regiment was billeted in the aerial defense academy.

- I understand you did some sightseeing in Nanking. Please tell us about that.

We know the regiment would be leaving Nanking on December 24. So we were permitted to go sightseeing in the city on one occasion.

We travelled in groups always with a leader. I was selected to lead a group of five or six men. I think it was on 20th that we went sightseeing.

- Did you see the area where the refugees were accommodated also what was the situation inside the city?

We did not see the refugee area, but the city was very peaceful. As Asahi Shimbun and other newspapers reported, peace had definitely been restored in Nanking.

Notice that Chinese workers are indifferent about the Japanese soldiers walking on the street.

The caption says, "Peace Restored in Nanking; Japanese soldiers distributing sweets to refugees" Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, December 24, 1937 edition

- Could you give us more details about the city?

I didn’t see many Chinese there. When we approached a park, we saw some stalls where vendors were selling merchandize to Japanese soldiers. I remember seeing a shoe repair stall and a barber shop.

- There is something I’d very much like to ask you. I understand you had a seal made.

Yes. At a shop that sold seals, I was encouraged to have one made commemorating our entry into Nanking. I ordered one made from water buffalo horn. They told me it would not be ready until the next day. So I went by myself to pick it up. I still have it.

- This is Mr. Kondo’s seal on the screen.

Yes, this is my seal.

- Since you were able to order that seal it must have been very peaceful and calm in the city.

I can’t believe thousands of people were slaughtered every day as some say they were when people were conducting their business so peacefully.

- Thank you very much

No gunshots, no fires, A brigade’s sojourn, city sightseeing

(Saito Toshitane)

-I understand that you are a member of headquarters’ staff of the 18th Infantry Brigade from Tsuruga. Where in Nanking were your headquarters located?

After Guanghua Gate was occupied, we set up brigade headquarters about 1km north of the gate inside the city. We instructed the 19th and 36th Infantry Regiments to station themselves outside the city.

- Usually headquarters are established at the rear, not on the front line.

Yes. They are usually set up at the rear of the regiments. It was unusual to position them as we did on the front line 1km away from combat units.

This is proof that order and calm had been restored to Nanking.

- So, it was safe to establish headquarters at the front line because the entire city was now safe. Now could you tell us about Regimental Commander Wakisaka’s visit to the safety zone?

I no longer remember the exact date, but it must have been around December 20 when Commander Wakisaka went on the tour of the city with only one attendant.

When he arrived at the Refugee Zone, he told the sentry to arrow hem to enter. The sentry asked, “Do you have a permit?”

When Commander Wakisaka answered “No,” the sentry said, “You can’t come in here without a permit.”

Commander Wakisaka abandoned his attempt to visit the Safety Zone and departed. He testified this incident later at the Tokyo Trials.

Regimental Commander Wakisaka on the screen Nanking Safety Zone - Were you permitted to leave headquarters?

Yes. Headquarters were going to move to the rear on 24th or 25th. So we received permission to leave the area. On December 20 or thereabouts, I left through Zhongshan Gate(中山門) with a party of five or six men. Headquarters personnel were extremely strict about roll call. We went to Zijinshan(紫金山), which is about 150m above sea level.

Then we paid our respects at Sun Yatsen’s Tomb. We could see the city of Nanking from there. We didn’t see any fires burning, nor did we hear gunshots. The city was calm.

- Thank you

No Chinese soldiers’ corpses anywhere; Tour of the city; Situation near camp

INAGAKI Kiyoshi

2nd Lieutenant, veterinary officer

16th Transport Regiment

16D (from Kyoto)

(Inagaki Kiyoshi)

- Where did the Transport Regiment operate in the context of the entire army I mean?

It was the usual order; infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineering and bringing up the rear, the Transport Regiment. We were the last six companies at the tail end of the regiment.

- When did you enter Nanking?

After the city fell, December 16, I think.

- Three days after, then.

I believe so.

- Which gate did you use and what was the situation then?

We entered through Zhongshan Gate.

- What were the people doing?

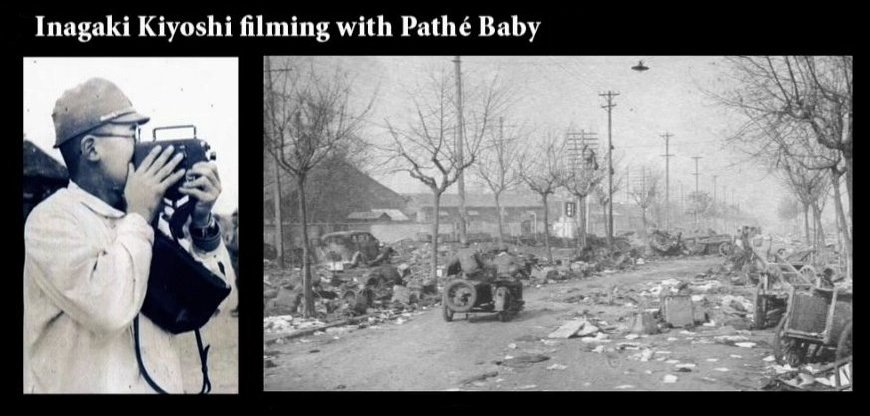

I have 18mm footage of this. I didn’t see any civilians near Zhongshan Gate at the time, not one.

- You didn’t see anyone. Where in the city were you garrisoned?

I don’t remember the route we took to get there, but our quarters were military academy near the city wall.

- Were there residents in the area?

There were houses in the area. But there was hardly anybody there when we arrived.

- How long were you in the city?

45 days.

[Note]

His stay in Nanking from December 16 to January 27 is particularly important considering that the Tokyo Trials determined that “wholesale massacres, individual murders, rape, looting and arson were committed by Japanese soldiers. […] This orgy of crime started with the capture of the City on the 13th December 1937 and did not cease until early in February 1938. In this period of six or seven weeks thousands of women were raped, upwards of 100,000 people were killed and untold property was stolen and burned.” (Judgment of 4 November, 1948)

During the same period, Mr. INAGAKI filmed various places of the City with a BMW side-car and, NO such “orgy” of mass murders and resultant piles of dead Chinese citizens or rape crimes are found in his films.- That’s about a month and a half.

Yes. I kept record of everything that happened. We were there until January 27.

-What type of work were you doing during that time?

After we got settled, I started making round-trips about five in all between depots in Hsia-Kwan on the banks of the Yangtze River and the depot in Nanking. The trip was 10km each way. I was transporting food for the soldiers and hay for the horses in the army cart.

- For the men and the horses? During those round trips, did you see corpses of Chinese soldiers?

I expected to see a few. So I was on the lookout for them. But I never saw any. I didn’t see any at Hsia-Kwan either.

- Not at Hsia-Kwan either?

Not at Hsia-Kwan, no. I shot some 18mm film, so please have a look at them.

- Do you have any comments about the exhibits at the Nanking Massacre Memorial Hall?

I saw a souvenir album issued by the Memorial Hall. It was compiled many years after the war. It contains diagrams with X marks at dozens of roadside locations. Next to the X marks are numbers in thousands and ten thousands indicating the number of victims.

I’m certain that I passed those locations three times in a BMW side car confiscated from the Chinese troops. It was assigned to me at the military academy. No one ever mentioned anything about corpses in connection with the locations marked with an X. Those locations were totally clear when I passed them. I saw no signs of corpses. Not even one.

"Rape of Nanking" by Iris Chang contains a map similar to the one mentioned by Mr. INAGAKI. ←Click to enlarge

- The residents of Nanking soon began returning to their homes. Could you tell us about that?

As Mr. Kondo said earlier, I think it was about two or three days after I entered the city. Little by little residents began returning.

I was inconvenience when the glass of my watch broke. I had a spare. But I took the watch to be repaired first thing, and I too had a water buffalo horn seal made. But, honestly I had forgotten completely about it until recently. Here is that seal.

I remembered it when Professor Hata Ikuhiko, who specializes in the Nanking controversy, mentioned having noticed the imprint of the seal in some of my records.

Mr. INAGAKI takes up to show his water buffalo horn seal - You’ve just heard what it was like in Nanking

Not even one gunshot - The Safety (Refugee) Zone

(Moderator)

Mr. Kita was with the 1st battalion 7th Infantry Regiment. This unit was stationed inside the Refugee Zone and was responsible for security there until it was transferred to Xuzhou (徐州).

I cannot think of anyone more appropriate than Mr. Kita to describe the situation in the Refugee Zone.

The Safety Zone is said to have been the scene of two incidents. The first involved the apprehension of Chinese troops who had infiltrated the Zone. The second involved abuse of civilians. These alleged incidents, which the Japanese were charged with having perpetrated at the Tokyo Trials, were referred to as the Rape of Nanking

First let’s hear from Mr. Kita about the sweep of the Safety Zone for enemy combatants.

When did the sweep of the Safety Zone begin and how long did it last?

The sweep of the Refugee Zone took place over three days; December 14, 15, and 16. It was an intensive sweep to be completed before the ceremonial entry and the memorial service for all war dead. During those three days we spent a great deal of time walking around the zone.

- Were you given special instructions in connection with the sweep?

(Mr. KITA)

Yes, we were. There were 7 rules we were to observe strictly.

- Respect the property of third party nations.

- Be considerate for the city’s residents.

- Avoid starting fires at all costs even inherently. Anyone violating this rule will be severely punished.

- All sweeps shall be directed by commissioned officers

- That means without a commissioned officer overseeing the operation, the sweep could not take place?

That is correct.

- What was the 5th rule?

No units without specific assignments are to enter the Safety Zone. Units from Toyama and Kanazawa took charge of the sweep. Our passwords were Toyama and Kanazawa.

The next rule concerned the sweep schedule. It states that soldiers must return to their quarters by a certain time in the evening.

The next rule was: Detain prisoners of war in one location; Request food for them from the division.

- It states that soldiers must return to the quarters by a certain time in the evening. Is that right?

Yes. The next one…this was a precaution, was: Avoid problems caused by unfamiliarity with the Chinese language. It meant; Make sure to have someone who speaks the language with you.

- Could you comment on the accusation that there was a great deal of looting by the Japanese soldiers?

Nothing of the sort!

- Couldn’t soldiers who strayed from units looted?

Absolutely not!

- Tell me about the apprehension of Chinese combatants.

Well, we found strugglers, defeated soldiers in houses with name plates.

- Name plates?

Yes. When we went into houses that had nameplates on them, we found machine guns and anti-aircraft machine guns made in Germany. They had weapons that we didn’t have.

Japanese Records show there were 50 truckloads of concealed weapon discovered after occupation of the City. - In houses with nameplates?

Especially houses with very large nameplates.

- How did you handle the strugglers?

Well, we knew you are soldiers right away because they are solidly built and suntanned. We have received instructions advising caution because officers wearing civilian clothes had infiltrated the Safety Zone.

- Then, the Chinese troops hiding in the Safety Zone concealed their weapons to avoid becoming prisoners of war. They changed to civilian clothing and hid. These are not prisoners of war. They were defeated combatants. It is appropriate to refer to them as unlawful combatants who are not protected by international law. They were apprehended and executed in accordance with international law as unlawful combatants.

- Next, I’d like Mr. Kita to tell us about the civilians in the Refugee Zone.

There were a lot of poor people in the Refugee Zone. Wealthy residents had fled to Hankow or Wuhan early on. The Refugee Zone was filled with poor people who didn’t have any means to evacuate.

Scenes the Japanese Soldiers Saw in Nanking Safety Zone

With those smiling faces and relaxed atomosphere, how can you say there were mass-murders?

↓ Click to enlarge.- Why were you there? Did you hear gunfire?

During the whole time I was there, I never heard a gunshot. I certainly didn’t use the gun.

- I understand that some of the residents who had sought refuge elsewhere begun returning. Could you tell us about that?

I think it was on 14th that they came back and started doing business. They operated barber shops, noodle stalls, things like that.

Questionnaire Results

(Moderator)

Next I’d like to tell you what we learned about the situation in Nanking from response to questionnaire about the Nanking Incident that we asked the veterans who participated in this event to complete.

First, about whether there was a massacre in Nanking. Here are the answers from 8 of the veterans:

Mr. Inagaki, “I neither heard of nor saw anything of the kind”;

Mr. Ichikawa, “I didn’t see anything like that.”

The other responses are similar. None of our veterans saw or heard of anything about the Massacre.

Whether they were inside the Safety Zone or outside it, they are unanimous in saying that they never witnessed a Massacre.

- When Tsukamoto Kouji(塚本浩次), Shanghai Expeditionary Army Judge advocate entrusted with the prosecution and punishment of infractions of military regulations, was asked at the Tokyo Trials about unlawful acts committed in Nanking, he testified that there had only been 10 cases. Since there were so few, it’s not surprising that none of the veterans here today heard about them.

- Next, I’d like to discuss the question of looting.

As you can see the words used for each response differ, but the meaning was all the same in all cases. All of our respondents believe that there was no looting because they neither saw nor heard of any.

Usually when looting takes place one of the most common targets is food. Therefore, I asked our veterans whether there had been sufficient supply of food, and almost all of them said there were plenty of rations.

Once order had been restored to Nanking and the situation became calmer, headquarters’ procurement activities ran smoothly.

Foreign records cite many cases in which cash was stolen. But Japanese soldiers had more cash from salary payments than they could spend. It’s hard to believe that Japanese soldiers would have stolen cash.

Foreign records also state that drunken soldiers entered the Safety Zone and committed violent acts there. But the Japanese soldiers were not permitted to leave their quarters when intoxicated. Also entry into the Safety Zone was severely restricted.

Thank you very much.

No assaults on civilians, murders, and looting

NAYA Masaru

Private 1st Class,

Infantry Gun platoon,

11th Company, III/7i, 9D

(Mr. NAYA)

- Did Japanese military personnel assault any civilians in the Safety Zone?

I am certain that no Japanese soldier assaulted a civilian resident.

Woman crawls out of underground air-raid shelter (Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, December 16, 1937 edition) A Japanese officer giving sweets to Nanking residents (Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, December 30, 1937 edition)

A View of Nanking Safety Zone on December 15, 1937 (Photo taken by Mainichi Shimbun Reporter SATO Shinju)

- What about the outside the Safety Zone?

There was not a sole outside the Safety Zone and there were hardly any Japanese soldiers outside the Safety Zone with the exception of the 7th Regiment. Most of them were not in the city for any length of time. I cannot imagine how any incident could have occurred.

- Thank you very much. Which regiment was responsible for security in the Safety Zone?

The 7th Regiment, which was famous for strict observance of military regulations.

- So the 7th Regiment known for strict observance of military regulations was responsible for security in the Safety Zone.

I cannot even imagine that Japanese Military, as an organization or as individuals, murdering 200,000 or 300,000 refugees.

I know that because there were 200,000 refugees in the Safety Zone and the population there never decreased in the slightest.

- Here says 300,000. What do you think of that?

Impossible!

- Thank you very much

[Note]

Japan’s records show that the estimated population of Nanking at mid-February, 1938 was 380,000. (Source: Nanking Special Service Unit Report)

Left: Tokyo Asahi Shimbun December 25, 1937 edition

Right: December 16, taken by SATO Shinju inside the Safety Zone

Nanking residents reveal no animosity toward the Japanese

NONAKA Shozaburo

Private 2nd Class,

Independent Transport Unit

2nd Regiment

(Moderator)

- Several months after the occupation of Nanking ended, in late January 1938, a man named Nonaka Shozaburo took a survey of Nanking residents to find out how they thought about the Japanese. I had planned to have him speak to us but he was unable to be here today. Mr. Nishimura Koyu will us about his work.

- Mr. Nonaka was attached to the 2nd Independent Transport Regiment, but he did not take part in the battle of Nanking.

- However, in late July 1938, his superior officer asked him to poll Nanking residents about the sentiments toward Japanese Military who had occupied Nanking for six months.

- With a company by that superior, he visited home in Nanking and conducted interviews

(Narrator)

My superior 2nd Lieutenant Toyonaga Takashi accompanied me about for four days. We visited 11 Chinese homes whose inhabitants I attempted to interview. I speak Chinese. In doing so, I discovered how the residents of Nanking felt about the Japanese several months after what is referred to as the Nanking Incident.

First of all, about the situation in Nanking at that time. The city was peaceful. There were a of Japanese soldiers there and there were new recruits. I was kept busy saluting at every encounter.

On Hanzhong Road the main street runs east to west I saw a lot of Japanese shops. There was a brothel and I noticed a Japanese-style bathhouse. A woman from Kumamoto Prefecture was sitting at the entrance, keeping watch over the premises.

There were a lot of people on the main street. I saw carriages and trucks, but few automobiles.

Left:Japanese soldier befriends Chinese family

Right:Bustling crowd on Hanzhong Road (published on March 21, 1938)

←larger map is available by clicking the image There didn’t seem to be much anti-Japanese sentiment. Women weren’t frightened at the sight of Japanese soldiers. Not the least one ran back into the houses.

We were able to walk around the city without exercising much caution. When we went out, we only had bayonets. We took them simply because they were attached to our belts, not because we thought we need them.

To find out people’s opinions of Japan I entered side streets from main streets, probably south of Hanzhong Road or east of Zhongshan Road.

No one seemed frightened or hostile when we knocked on doors. Chinese homes were small and dirty. The standard of living was much lower than that of Japan then. The walls were made out of earth or formed into bricks. There were hardly any windows. Inside the houses it was dark. The ceiling was low and the only illumination came from a naked 20-watt light bulb. Even though they didn’t have much to lose, when we interviewed them, the people told us that they left Nanking when the Japanese approached the city.

When order was restored, they returned to Nanking: some of them three months ago; others two months ago; and still others more recently.

Thank you very much.

- The Chinese claim that one third of Nanking was destroyed by fire. But according to Mr. Nonaka’s testimony, when the city’s residents returned, their homes were still there intact.

A Chinese boy in Nanking enjoys kinship with Matsushima Unit

(Tokyo Asahi Shimbun December 21,1937 edition)

Local procurement of food - Requisitioning governed by strict rules

(Moderator)

- The supply line for Japanese soldiers advancing to Nanking was undependable. Then men were forced to obtain locally. Critics often claim this exigency led the soldiers to confiscate or steal food. Mr. Saito Toshitane, then a HQ staff member with the 18th Infantry Brigade from Tsuruga will speak to us on this topic.

- What was the food situation during your travels from Shanghai to Jintan (金壇) and Nanking?

(SAITO Toshitane)

After November 15 when the Shanghai Conflict ended, we attacked Kunshan(崑山)and then pursued the Chinese retreating toward Nanking. Until we reached Jintan on about December 2, we had enough food. But then our troubles began. It was hard to find food for the men on the front line and the HQ staff.

- Once you arrived at Jintan, your supply stuff coming down. What was the policy for requisitioning food?

We had received instructions from Brigade HQ which we obeyed. I made the list of instructions that I remember.

First, procurement was to take place at locations within sight of HQ for safety sake

Second, we were to restrict requisition of food in inhabited areas to one third of what was available. We were cautioned not to take too much.

Third, we were not permitted to break into unoccupied homes. We were authorized to take half of whatever we found outside residence. When we did so, we were instructed to post a voucher at the sight.

Fourth, we were instructed to leave a list of items that we had confiscated so that the Pacification Unit would know how much to pay residents who submitted the claim. I laid down the requisition of voucher used then to prepare this facsimile.

The top line says item and the bottom says amount. The voucher is divided into two sections; A and B. In the A Section, it says, “To receive payment for the items taken, take this voucher to the Pacification Unit of the Japanese Amy.” The seal of the HQ, 18th Infantry Brigade, Imperial Japanese Army, is affixed to it. Column B contains the same information in Chinese.

Our soldiers tore this voucher in half affixing the Chinese half to the house, and taking the other half with them. The system was set up so that payment could be made after the fact.

That is correct.

The fifth was: once you have taken the food, return to unit. Then go to the HQ and submit the requisition goods and itemized list for inspection. First Lieutenant Igarashi was the inspector. He checked to make sure that the items and the amounts were correct. Even a small error would earn a scolding.

- You would see how strict the authorities were about the items in column A and B have been absolutely precise.

Thank you very much.

Prisoners of war escape, the prisoner problem

(Moderator)

- 16th Division Commander Nakajima has been reported as having said “Our policy is to take no prisoners” as 30th Brigade order that reads “No units may take prisoners of war unless so instructed by the Division” has also been cited. These were misinterpreted and taken out of the context to the point that prevailing interpretation became “Japanese policy was to immediately execute all enemy combatants who surrendered.”

- In connection with this topic, I would like to present Mr. Inagaki Kiyoshi’s film of prison camp and his testimony how prisoner of war was actually handled At the time Mr. Inagaki was a veterinary officer attached to the 16th Division.

- Please tell us where the prison camp you saw was located and how many prisoners it accommodated.

(Mr. INAGAKI)

I touched upon this earlier, but before we entered through Zongshan Gate, we have been bivouacking at Shangqilinmen(上麒麟門), about 10km from Zongshan Gate.

I think the detention camp was directly in front of our camp. You know this is true because I took some 9.5mm film with my Pathe Baby camera. This was a French camera, a forerunner of 8mm cameras.

- About how many prisoners were detained there?

I don’t know for certain because I never counted them. But I think there were somewhere between 800 and 1,000 of them.

- Were they wearing uniforms or civilian clothing?

They were all wearing uniforms.

- Then, was the Transport Regiment guarding the prison camp?

Yes. According to my records, that was on December 16. Our Transport Regiment was ordered to provide guards for the prison camp.

- Perhaps I’m not sure it is my ignorance, but my impression was that the Transport Units are not Combat units. Wasn’t it easy for the prisoners in custody to escape?

Exactly, we were divided into 30 details each led by a private 1st class or a corporal. There were 6 squads. The detail and squad commanders had cavalry rifles. They were about 10cm shorter than the more common type 38 Rifle used by the infantry. Cavalry men used them on horseback. Only detail and squad commanders had them.

There were only 36 rifles. 14 or 15 men were assigned to sentry duty. One of them, who is still alive and lives in Kyoto, told Professor Higashi-nakano that by morning half the prisoners had escaped. What a carefree attitude!

But I think it was mistake to entrust Transport Regiment men like us would security the prison camp. My guess is that they figured if the prisoners are going to escape anyway, we might as well put the Transport Regiment in charge of them. And I am not the only one who thinks so. I’ve heard Imamura Kozo in Kyoto say the same thing.

- I am a little surprised. What you said seems almost funny.

Listen. I’m sure there was a huge gap between what the men on the front line were thinking and what those of us in the rear were thinking. I am embarrassed to admit it. But that is the way it was

- Please tell us about the prisoners of war at Anzhuang (安庄)in Xuzhou. (徐州)

Afterwards there was a battle at Xuzhou in May. This is the famous conflict that Hino Ashihei wrote about in his soldier trilogy.

It happened the day before we reach Xuzhou. As a matter of fact we left Nanking and at Anzhuang, 189 soldiers surrendered to us. I filmed them with my 8mm camera. Most of them were farmers from Shandong, the province adjoining Xuzhou.

I don’t think there was one proper soldier amongst them. So we took prisoners. The majority of them were drafted when they came from Shandong seeking seasonal work. Following the commanding officer’s orders, we detained all of them and did body checks. It was very unpleasant for us, because they were filthy and crawling with lice.

Since we had to move on, we turned them over to a guard unit. We released all of them that night. We didn’t harm any of them.

Thank you very much.

Now we show you the video taken by Mr. Inagaki. It’s a movie clip filmed by Mr. Inagaki at that time.

This is 8mm film. I shot it between the time I departed from Nanking and my return home to Kyoto in August, 1939.

That is Zijinshan 紫金山in the background. In front is the Military Academy with the 6-company Transport Regiment was quartered. There were 350 men in our company and 426 horses. When you multiply those numbers by 6, there were 6 companies and add the regimental HQ staff, the total is quite high.

These are barracks. These are our quarters. Those are reserve horses at the rear. The men with the rifles on the shoulders are the detail and squad commanders. This is the village where we camped. This was filmed during the march to Nanking.

Here we finally approaching Nanking. The city walls are in sight.

This is probably near Shangqilinmen. You can see our camp. These are trucks moving toward the front-line.

That is Ohara, a medic. That’s me. That’s Ohara and Warrant Officer Okuda a medical corpsman.

I don’t remember where this was taken. I filmed this outside Nanking. This is the sign for a prisoner detention camp. I remembered that a lot of enemy prisoners were housed in a large building. I have still photographs for this too.

Here is our entry into Nanking.

This is one of Nanking’s gates. We entered through Zongshan Gate. This is me.

This is part of Zongshan Gate that was demolished.

This is our unit entering Nanking. The man waving is my aide Murayama.

I shot this inside the city.

This is my unit marching inside the city.

This is my unit in formation.

The bearded man is Sergeant Major Takayama.

This is from our company. This is the light tank unit; The Fujita Unit.

These are our two squad commanders.

The is the Nanking Wharf where military supplies were loaded or unloaded

These are military supplies, ammunition, or perhaps fuel. This is floats from the Yangtze River. I never saw any corpses there.

This is a flock of magpies on a dead tree outside Nanking. The magpies here were much smaller than the ones in Japan.

That’s a Japanese aircraft.

This is Zijinshan viewed from the Military Academy.

I don’t remember what this building was. This is the part of the city wall that leads to Hsian-wu Lake. 玄武湖 I think that is the bridge that spans Hsian-wu Lake

This is one of the Nationalist Government buildings. 16th Division HQ were located here. I visited here several times.

This is the 16th Regiment joint memorial service held after the battle ended.

This was filmed the day before the battle at Xuzhou.

This shows 189 enemy soldiers raising their arms and surrendering. This is exactly how it happened. They’re all holding pieces of wide cross against their chests. As you can see there is not one proper soldier there. They hadn’t received any training at all.

We had an awful time because covered wit lice, although we had lice too.

We had to move on. So we turned the prisoners over to a guard unit. They were all released at night.

Testimonies of 102 Nanking Veterans pronounced fantasy literature

ICHIKAWA Jihei

Sergeant,

Commander, 1st Platoon

5th Company,

II/33i, 16D

(Moderator)

We’ve come to the last part of our program. Nishimura Koyu will present our next topic.

(Narrator)

Here are Ichikawa Jihei’s comments on “In Search of Repressed Memories of the Battle of Nanking: Testimonies of 102 Former Soldiers by Matsuoka Tamaki “

“Testimonies of 102 Former Soldiers” is fantasy literature. I cannot believe soldiers interviewed actually fought in the Battle of Nanking. I can say with absolute certainty that what he wrote about the 33rd Regiment is fiction.

Here are my reasons.

Since the members of our unit are all from the same prefecture, we all know each other well and enjoyed true solidarity.

If one of us had been interviewed, he would have contacted all the others. I’ve never heard anything about the interview.

This testimony is suspicious for the following reasons.

1. The description of facts and events leads me to doubt that the people fought on the Battle of Nanking.

2. Most of the personal names as well as details that would identify the units have been withheld. With methods like this, it is possible to create any number of imaginary characters.

3. The interviews are said to have taken place in the year 2000. But there are no more than 30 veterans of the Battle of Nanking left in Mie Prefecture. The book claims that 59 of the 102 men whose testimonies were included with the 33rd Regiment. The disparity is obvious.

And looking at the statements, I noticed so many mistakes. One would expect the memories of anyone who fought and risked his life in Nanking to remain vivid forever.

Thank you very much.

(Moderator)

- The testimony you just heard was provided by Ichikawa Jihei. We asked him to comment on the book: “In Search of Repressed Memories of the Battle of Nanking: the Testimonies of 102 Former Soldiers” before the book gains undeserved credence.

Today you heard in great detail how the Japanese fought in the battle of Nanking and what they experienced there.

I was deeply moved by the tenacity of the heroes who first occupied Nanking.

I also learned that after the battle they interacted amicably with the city’s residents and observed military regulations to the letter.

As the Japanese, I would like to express my profound gratitude to and respect for these valiant heroes

Thank you very much for your attention.

- End of Presentation -

|

|

To the top of this page |

|

|

Return to Home |